Gun Laws, Crime Rate and The Long Gun Registry

Lets do some thinking here according to CTV the gun registry is accessed by Police 11,500 times per day. Now let's multiply that by 365 (the number of days in a year) which equals 4,197,500. The population of Canada is approximately 34,108,800.

Per Year Police access the gun registry on approximately 12.31 percent of the population. A number that is surprizingly close to the percentage of violent crimes.

According to Wikipedia in 2006 there were 2,457,787 crimes reported, 48% were property crimes and 12.6% were violent crimes.

These numbers require further investigation into the events and if a firearm that was legally obtained was involved in a crime, or if Police have nothing better to do then check on the status of legally owned firearms?

Are Police claiming "ALL VIOLENT CRIMES" involve firearms or "legally owned firearms" are owned only by criminals?

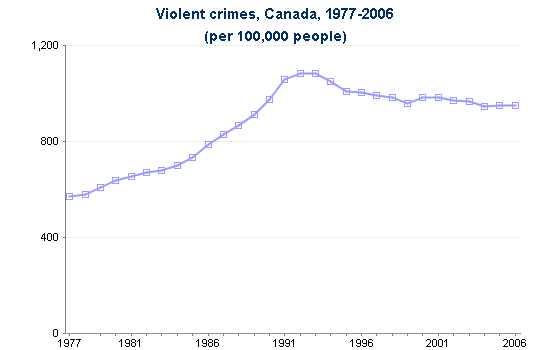

It has been argued that with Gun Control violent crime would increase, Advocates of Gun Control claim otherwise, but according to Statistics Canada crime rates are increasing in Canada

Compare the dates of the increases as compared to Gun Control Legislation.

1977, 1991 and 1995 each time we implemented stricter regulations the violent crime rate increased and levelled off in 1996-97.

I did not include statistics to the 1969 implementation of the change to prohibited status of machine guns.

If you care to look it up the violent crime rate was much lower

Most of the violence was committed by terrorist groups like the FLQ who preferred bombs over guns.

Source: Statistics Canada. Crime statistics, by detailed offences, annual (CANSIM Table 252-0013). Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2007.

Who Do we believe?

Study claiming crime on the rise gets hung out to dry by experts in the field

By Bruce Cheadle, The Canadian Press | The Canadian Press

OTTAWA - Criminologists say a study that attacks the long-standing measurement of Canada's crime rate is "highly politicized" and without statistical merit.

Crime and punishment appears to be shaping up as a defining ballot question whenever Canadians next go to the polls, so the statistically unorthodox claim that violent crime is on the rise is noteworthy.

Scott Newark, a former Harper government adviser who counts himself a contributor to the Conservatives' 2006 justice platform, released the 29-page study last week questioning Statistics Canada's methodology on compiling crime stats.

Newark asserts that "many of the most common conclusions that are drawn about crime in Canada are in fact incorrect or badly distorted."

"Serious violent crime is increasing," the former executive officer of the Canadian Police Association flatly asserts.

While Newark's report for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute was given prominent coverage by both the Globe and Mail and National Post newspapers, the wider academic community that relies on the data was not consulted.

Their reviews are scathing.

"It's really badly done. It's embarrassing, actually," said Neil Boyd, a criminologist at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver.

"For anybody who follows what Statistics Canada puts out, it's a grossly unfair characterization. It mixes up key concepts...."

"That's what struck me. This is a highly politicized document that isn't paying attention to relevant data."

James Hackler, a criminology professor at the University of Victoria, wrote a letter to the Globe on Friday saying the study illustrates "ideological bias."

In an interview, Hackler said studies across the Western world clearly show crime rates in decline, although criminologists differ on the reasons.

Newark's study, he said, "is like saying the world is flat. This is not a credible report."

And Rosemary Gartner, a criminologist whose course load at the University of Toronto includes methodology, appeared dumbfounded by Newark's repeated insinuations that Statistics Canada is manipulating the data.

"He makes a reference how indeed it serves their institutional purposes to show that crime is going down," Gartner said in an interview.

"What the hell does that mean? Did it serve StatsCan's institutional needs when crime was skyrocketing in the early 1990s?"

Newark, whose political advocacy for "tough on crime" policy goes back to the Mike Harris Conservative government in Ontario, bases his critique on some key assertions:

— Under-reporting of crimes because only the most serious charge from any one incident is counted.

— Data that Statistics Canada once included in its annual Juristat report is no longer published.

— The Crime Severity Index, based on sentence length for particular crimes, is a subjective measurement influenced by lenient judges.

— StatsCan's after-the-fact upward revisions of crime data tend to exaggerate falling crime rates from year to year.

Julie McAuley, director of the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics at Statistics Canada, and John Turner, chief of the agency's policing services program, addressed Newark's claims one by one:

— Reporting only the most serious charge from a multiple-charge incident is somewhat problematic, McAuley said, but it's been handled this same way since 1962 and conforms with other jurisdictions such as the U.S. The recording method reduces variations in charging practices between police services.

— All StatsCan data from the past 30 years is available upon request. It just can't all go in a single publication.

— The Crime Severity Index uses national sentencing averages to avoid local judicial variations. The index was adopted in consultation with the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police and all the provinces. "The principle founding mandate behind the whole crime index was that it had to be objective," said Turner.

— Over the last decade, annual data revisions have increased crime stats six times and decreased them four times, so the revisions cut both ways.

Gartner, who teaches methodology, also took Newark to task for continually switching his comparison years, and for selectively comparing incident numbers without accounting for population growth.

She also notes that Newark uses StatsCan's General Social Survey findings to indicate unreported crime is a problem. But, she said, he "completely ignores the fact that the (same) GSS victimization survey shows violent crime and other crimes have been going down."

Boyd, moreover, said the survey's findings on unreported crime have barely budged over the years.

Gartner and Boyd both agree with Newark that it would be great to have far more detailed crime data, particularly profiling who is committing crime.

"The revisions he's calling for would require a huge infusion of cash to every single police force in Canada, as well as to StatsCan," said Garner. "I'd love it. I'm a criminologist. The more data the better."

"But the (report's) implication is: 'They can do this, they should have been doing this, it's not clear why they haven't been doing this.'

"He knows better."

Homicide rates appear to vary with unemployment, alcohol consumption

During the past four decades, years with higher rates of per capita alcohol consumption and unemployment tended to be associated with higher rates of homicide.

Results of this study suggest that there is a small, yet statistically significant association between homicide, alcohol consumption and unemployment such that when rates of alcohol consumption and unemployment increase, so too does homicide.

Alcohol use has previously been associated more often with violent crime than property crime because of the disinhibiting effect it has on cognition and perceptions. Likewise, unemployment has been associated with stress, exclusion and social withdrawal.

The report Exploring Crime Patterns in Canada (85-561-MIE2005005, free), which is part of the Crime and Justice Research Paper Series is now available online. From the Our products and services page, under Browse our Internet publications, choose Free, then Justice.

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts or methods of this release, contact Client Services (1-800-387-2231; 613-951-9023) at the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.